Wells

Poking

Holes

I

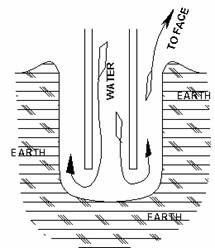

put down the above-mentioned garden well through a technique known as

“jetting”. Jetting is what happens when you push a gushing water

hose against the ground and it begins to dig its way in. Water erodes

the soil directly in front of the blast, and washes it back out of

the hole around the hose, and into your face and shoes.

With

a handful of fittings from a hardware store and a few simple hand

tools, I was able to connect the end of the garden hose to a six-foot

piece of ½” galvanized pipe, and then add other bits and pieces to

the drill string as the work progressed.

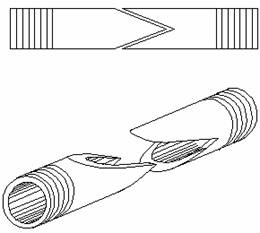

By

cutting a short piece of pipe (usually called a “nipple” – I

didn’t name it - with a hacksaw as shown, and coupling either piece

to the end of the pipe, the process was considerably faster.

It

helped to repeatedly raise the pipe a couple feet and force it

downward into the hole. This caused the inertia of the water in the

pipe to exert tremendous force against the bottom, and also helped

the sharp edges of the pipe to cut.

In

addition, I would twist the drill string clockwise as it struck the

bottom of the hole and return it slightly counter-clockwise as I

raised it. This would help the bit cut, while insuring that none of

the pipe fittings twisted loose. A large pair of vice-grip pliers

made an excellent handle.

One

other tip: Don’t drop any tools down the hole. It’s OK to be a

klutz, as long as you know you’re a klutz and take the time to

compensate. I made an anti-klutz shield from a piece of heavy plywood

with a drill-string-sized hole in it. By setting the plywood up on

some blocks, I was allowed room for the mud and water to escape to

somewhere besides my shoes.

There

is a story about this well for the amusement of those who would

considering me a nut or a liar, the amazement of those into weird, or

the interest of those of mystical experience. This has nothing to do

with anything technical, so the none-of-the-aboves can skip this.

When

I was considering the site for this well I was assuming I’d have to

go down a significant distance. A couple hundred feet in one

direction there was a century-old hand-dug well that went down 65

feet before striking water. About a hundred and fifty yards in

another direction, there was a well that went down 45 feet, and

produced plenty of water.

In

choosing a spot for this well I first considered consulting a “water

witch” as my dad had tried in the past, but that seemed a little

too occult for my tastes. So I figured I could just pray and ask God

where He put the water (for real). I tend to push it with almost

anybody, and in all fairness that includes God. So I figured that if

He’s really God, he could put the water wherever He wanted to.

“OK

God, I’d like it near that tree, not too far from the door of this

shack”. I struck water at six feet, but the day was young so I

continued to a depth of twenty eight feet – six hours and a sore

back later. I became suspicious about the value of the other

twenty-two feet, when everything below the six foot level was solid –

albeit soft – decomposed granite.

It

turned out that this layer of soft rock had trapped a stream of

surface water that I was able to trace to a mild seep a little

distance off, where the surface of the ground dropped away slightly.

The only evidence of this was a type of plant normally found only

near streams or ponds. With the combination of a 12V bilge pump and

the hand pump working simultaneously I was never able to pump it dry

while filling a 55 gal. drum, during an entire Southern California

summer. Thanks God.

Survival

itself is not life – a rock can “survive”, but life is a

platform, for so much more.

A

Little Bit More

It's

nice to be able to put down a well when you have an unlimited supply

of pressurized water, but it makes a little more sense to learn how

to do it in places where water has to be imported in buckets.

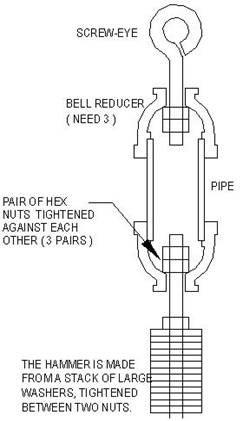

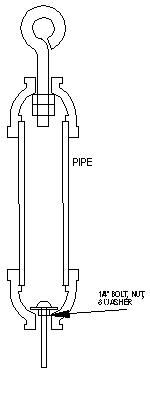

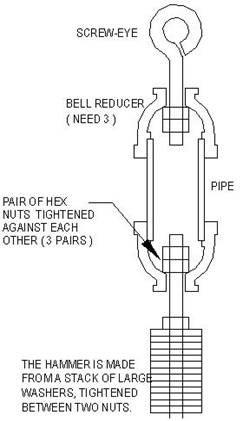

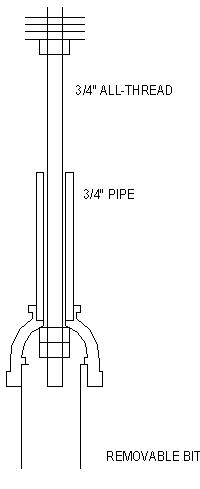

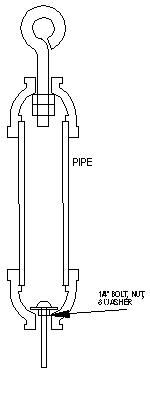

A

drop-bit consists of a cutting-end, connected to a hammer-end. The

whole thing is then dropped down the hole on a rope or cable. As the

cutter hits the bottom, the hammer lands on top of it and gives it

another kick. The hammer portion is then raised and lowered

repeatedly to drive the cutter into the rock or soil. This hammer

action also works in the up-direction, to free the bit when it gets

stuck in the bottom of the hole.

Periodically,

the assembly is withdrawn, and the section below the 1-1/4"

coupler is removed and emptied.

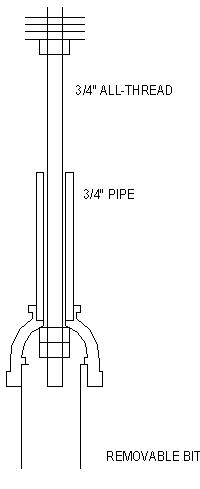

Although

I have produced a bit that basically works, I feel there is room for

a lot of improvement. This assembly was made from

off-the-shelf hardware available from most home-improvement stores.

The photo shows what I've developed so far. Note the spare bit above

and to the left of the hammer assembly.

The

bit is considered "dry" because a continuous stream of

water is not being forced down a drill-string. Sometimes

however, a half-gallon or so might be poured down the hole to soften

the bottom. It is helpful at such times to pour the water down the

rope, so it does not fill the bottom with mud washed from the sides

of the hole.

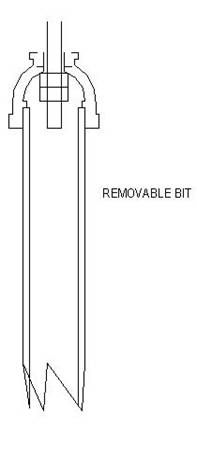

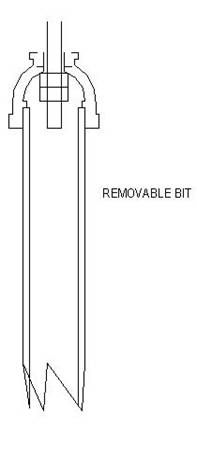

You

will find that different soil/rock conditions will need different

cutter sections. Some will produce a nice core from a round empty

cutter, and others will require a pair of flaps to trap loose soil or

mud. In some cases you might do cutting with one bit and soil

removal with another.

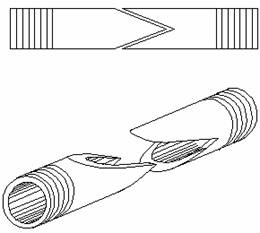

For

a basic cutter, cut four teeth in the bit at the bottom.

I

made a bit for removing loosened soil and thick mud by threading a

carriage-bolt through the bit and a couple of sheet-metal flaps, a

couple inches above the bottom.

The

flaps wrapped around the bolt the same way hinge pieces wrap around

their pin.

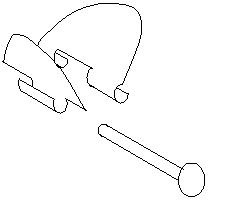

A

different form that could be helpful for getting out fine sand and

mud, after you've found the water table, is shown here.

This mud bucket is

lowered on its own rope.

This mud bucket is

lowered on its own rope.

Make

no mistake: This well is a lot of work, and could certainly be

improved. It does however, make poking a hole in the ground

possible.

During

the process, be fanatical about regularly checking the status of all

joints, so you don't wind up with a half-drilled well being blocked

by a half-there drill assembly. I didn’t learn this lesson the easy

way.

Although individual household

storage may be practical at any level of development, it would be

important for the village to own the source of water and the means of

distributing it.

With the source of

water secure, a village-wide plumbing system could be developed.

Optimally however, each residence should have storage for both

potable and non-potable water. Such distributed storage would

increase accountability and awareness for the conservation of this

most precious and limited commodity. There should also be some

provision for the collection and recycling of grey-water for

agricultural applications. Bottom line: Use every drop wisely.

Such care and concerns may

be unthinkable in our current paradigm of plenty, but they will

ultimately concern us all, as they currently concern most of the

world.

This mud bucket is

lowered on its own rope.

This mud bucket is

lowered on its own rope.